Parasitology

Compiled by Susan Mikota DVM, Vijitha Perera DVM and Willem Schaftenaar DVM

Nits (lice eggs) on the skin of an Asian elephant calf

Adult lice

Horseflies (Tabanids)

Horseflies are large blood sucking flies. They are especially active on hot, bright, humid days. Their bite is painful and irritating and may result in the formation of nodules on the surface of the skin (Dangolla 2006). Tabanids are the intermediate host for Trypanosoma evansii, a blood parasite that causes trypanosomiasis (also called surra or thut) in elephants (Fowler, 2006).

Screwworm flies/maggots

Screwworm flies (Chrysomya bezziana) lay eggs in and around open wounds. When they hatch, the maggots burrow and feed on (dead) tissue. Maggot-infested wounds should be flushed and maggots removed manually. Hydrogen peroxide or ether will coax maggots from deeper wound crevices. Zoosamex spray (Wokwel Ptd. Ltd. Singapore) has been used in Sri Lanka to kill maggots that have penetrated deep into tissue (Silva and Dangolla, 2006). Remove necrotic (dead) tissue and thoroughly clean the wound at least daily.

Dipterous larva may produce small nodular eruptions from which larva can be expressed (Chakraborty, 2003). When the larva is mature, the fly exits, leaving a small hole in the skin. Secondary infections may develop that are usually bacterial, but mycotic dermatitis has also been recorded.

Chrysomya bezziana adult flies and larvae (maggots) (African species, Wikipedia)

Ticks (Amblyomma sp.)

Ticks may be found behind the ears, on the shoulder or upper hind leg or in the perineal area (near the anus). They should be removed manually.

Species that have been found on African elephants are: Amblyoma Tholloni and Dermacentor circumguttus. Other species that have been found on elephants are: Amblyoma asterion, A. cohaerens, A. gemma, A. nuttallii, A. paulopunctatum, A. sparsum, A. variegatum, Boophilus microplus, Dermacentor rhinocerinus, Haemophysalis leachii, Rhipicephalus appendiculatus, R. compositus, R. humeralis, R. longus, R. maculatus, R. muehlensi, R. parvus, R. pulchellus, R. snegalensis, and R. simus (Fowler, 2006). Amblyoma tholloni is known to transmit Cowdria ruminantium.

Ectoparasites

Lice

Lice (Haematomyzus elephantis) are small wingless insects about 3 mm long. They are transmitted between elephants by close body contact. Lice may be found behind the ears, at the base of the tail, or anywhere there are folds in the skin. Lice can cause dermatitis and dry scaly skin. Elephants may be restless with frequent scratching. If lice are present around the eyelids, scratching may cause damage to the cornea. Frequent bathing, making sure to scrub behind the ears and other likely sites can help to remove lice. Flumethrin, a pyrethroid insecticide commonly used in dog and cat flea products, can be used topically. Heavy infestations can be treated with ivermectin given SQ or orally (Karesh and Robinson, 1985). Ivermectin kills nymphs and adults but not eggs (also called nits) so treatment should be repeated in 3–4 weeks when the next batch of eggs hatch. Lice are host-specific.

Fleas

Fleas are wingless insects about 1.5–4 mm in size. Fleas are not host specific so fleas from dogs or cats may infest elephants. Elephants can become infested with fleas by walking through an area contaminated with flea eggs or pupae or by close body contact with other elephants that have fleas. Fleas may cause the elephant to scratch and swelling and redness may be seen at sites where fleas have bitten. Fleas are blood-sucking parasites so a heavy infestation could cause anemia in a small calf. Ivermectin can be administered but attempts should also be made to clean up the environment and keep flea-infested dogs or cats away.

The presence of adult ascarid worms in the stool.

Microscopic examination of the faecal sample showing the presence of T. elephantis ova (X40).

Strongyles

There are several species of parasites that have strongyle-type eggs. Other than for research purposes, it is not important to determine the genus and species. Adults are found in the stomach, small or large intestine, or cecum depending on the species. Larvae hatch from eggs passed in the feces and elephants become infected by eating larvae on forage. Any of the broad spectrum anthelmintics including albendazole, fenbendazole, mebendazole, or ivermectin should be effective.

A severe Parabronema smithi infection was reported in free ranging elephants in Sri Lanka (Perera et al. 2015). At necropsy intensively spread caseous ulcers were found in the stomach wall in nine animals. It was the only gross suspected lesion of eight of them. The size of those ulcers varied between 0.4 - 8 cm. The margins of ulcers were elevated and the tiny parasites were observed in the ulcers as well as nearby mucosa of the inner stomach wall. Of the nine animals, three were male and six were females. The ages of the males were 2, 6 and 14 years. The females were older: four were over 30 years and two of them about 20 years old. Four of these females were also lactating. All the infected animals were emaciated.

Another member of the strogylides, Grammocephalus hybridatus, was found in the liver af a 15 yr-old female Asian elephant in India. Worm eggs were found in the rectum. Click here to read the full report.

Parabronema smithi associated ulcers in the stomach of an Asian elephant cow. (Perera 2018)

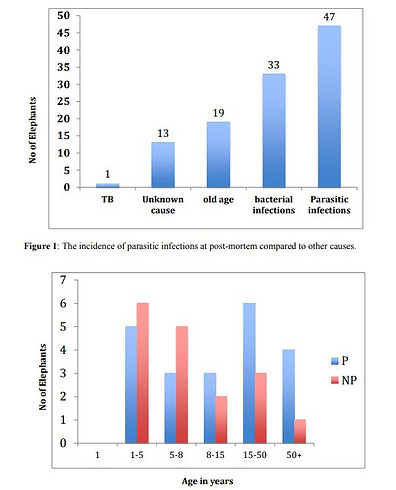

Comparisson of Parabronema positive with other parasite infections (Fasciola, Anoplocephala, Bathmostomum) at post-mortem (Perera 2018)

Strongyle egg in fecal sample (Dr. Jacob Alexander)

Strongyle worm in elephant feces (Dr. Vijitha Perera)

Strongyle worms in the submucosa of the intestines of an Asian elephant (Dr. Vijitha Perera)

Strongyle worms in feces. Many worms can be found after a successful antihelminth treatment (Dr. Vijitha Perera)

Cyathostomides

Several Cyathostomid species, belonging to the Strongylidae family, have been found in the gastro-intestinal tract in Asian elephants (Chel H.M et al, 2020).

Strongyloides

Strongyloides are small 1-2.5 mm) nematodes with two forms – a parasitic form that lives in the intestinal tract and a free-living form found in the soil. Elephants become infected by ingesting infective larvae or larvae may penetrate through the skin. From the intestine, larvae may migrate to other tissues including the mammary gland and may be found in milk, another means of transmission to calves. Strongyloides are usually harmless in adults but in orphans who are weak or sick they may cause a problem. Any of the broad spectrum anthelmintics including albendazole, fenbendazole, mebendazole, or ivermectin can be used.

Hookworms (Bunostomum spp.)

Hookworms are small and round and live in the intestines. Elephants are infected by ingesting larvae on forage or when larvae penetrate skin. They are blood sucking parasites so can cause anemia and be very harmful to young calves. Any of the broad spectrum anthelmintics including albendazole, fenbendazole, mebendazole, or ivermectin can be used.

Ankylostoma egg in elephant fecal sample (M. Ashokkumar, Centre for Wildlife Studies, Kerala Vet. and Animal Sciences University, Pookode, Wayanad

Trematodes

Flukes

Elephants can be infected with Fasciola jacksoni unique to elephants, or Fasciola hepatica common to domestic livestock. Adult flukes live in the bile ducts. Eggs are passed in the feces and must be deposited in water for the next phase of the life cycle that also requires snails which act as an intermediary host. Elephants become infected by ingesting water or forage harboring metacercaria, the infective stage.

Acute clinical signs include anorexia, constipation, diarrhea, anemia, icterus (yellow color of mucous membranes), anemia, and death. The chronic form is characterized by anemia, anorexia, weight loss and either constipation or diarrhea. Mucous membranes may be pale or icteric and ventral edema may be present (Fowler, 2006).

Flukes have characteristic eggs. Because fluke eggs are heavy, sedimentation vs. flotation techniques may be needed for diagnosis. Albendazole, trichlorbendazole, or oxyclozanide can be used for treatment which should be repeated in 45-60 days.

Fasciola hepatica collected from the liver from an Asian elephant (Dr. Vijitha Perera)

A case of Fasciolasis in African elephants

(Windsor et al. 1976)

A group of wild, young calves were imported in the UK from Africa in 1972. Shortly after arrival two died and they were found to be carrying heavy burdens of the intestinal fluke Protojasciola robusta. One male and eight females were moved and housed in another park in the UK. The females were in rather poor condition and showed marked oedema of the abdomen first apparent as a fairly discrete area around the umbilicus but spreading in one animal to include the entire ventral abdomen. No other clinical signs could be detected. Faeces samples were collected; no significant bacteria were isolated but numerous fluke eggs were seen. Although wild elephants normally carry fairly heavy parasite burdens, it was concluded that malnutrition and captivity might have allowed the parasites to assume a more significant role and cause the clinical signs. No reference to the control of this parasite could be found. Since rafoxanide (Flukanide, Merck, Sharp &Dohme) has been reported to be palatable and effective against fluke, this drug was chosen for the attempted treatment. It was arbitrarily decided to use 4 ozper head (this was equivalent to 3 mgfk, which is approximately half the recommended level for bovines), which was offered in a maize gruel to whicha large quantity of sugar had been added. Faecal examination one week later still revealed the presence of fluke eggs and the treatment was repeated. Subsequent examinations were made on three occasions at monthly intervals but no fluke eggs were seen. There was a marked improvement in appetite and physical condition though the oedema in one animal took six weeks to disappear.

Paramphiostomes

Paramphiostomes are flatworms/flukes with a life cycle similar to Fasciola. There is very little known about this parasite in elephants in the literature. It is commonly a problem in ruminants (stomach or rumen fluke). Paramphiostomes have a similar life cycle to Fasciola and should be susceptible to the same anthelminitics.

Trematoda: Amphistomida

Hawkesius hawkesi is the only representative of the amphistomata found in elephants. It has been described in Sumatran elephants (Matsua, 1997) and elephants in Vietnam (Sey, 1985). Its clinical relevance is unknown. It was found in the colon of a 17 yr-old Asian elephant in a European zoo, that had arrived 5 years before from Singapore Zoo: about 40 parasites of the species Hawkesius hawkesi (Trematoda, Digenea, fam. Paramphistomatidae) were found in the very cranial part of the colon. Many small (few mm diameter) nodules, with a darker colored central area were found in the surrounding areas (Willem Schaftenaar).

Fasciola hepatica collected from the liver from an Asian elephant (Dr. Vijitha Perera)

Fasciola hepatica piled up in a hepatic bile duct of an Asian elephant (Dr. Vijitha Perera)

Trematode egg in feces of Asian elephant (Dr. Jacob Alexander)

Paramphistomum specimen from the liver of an Asian elephant (Dr. Vijitha Perera)

Hawkesius hawkesi specimen in the cranial part of the colon of an Asian elephant in a European zoo, 5 years after its arrival from Singapore Zoo (Willem Schaftenaar).

Cestodes (Anoplocephala spp.)

Anoplocephala are large flat segmented tapeworms that live in the intestines. Tapeworm segments can sometimes break off and can be seem grossly in the feces. Elephants pass tapeworm eggs in the feces which are ingested by mites in which the egg matures into a cysticercoid. Elephants become infected by eating forage harboring the mites and cysticercoid larvae. While tapeworms are generally thought to cause little pathology, heavy infections in young calves can be serious and can cause impactions (Warren et al., 1996). Praziquantel is the anthelmintic of choice.

Tape worms found in the small intestines of an Asian elephant (Dr. Vijitha Perera)

Cestode eggs (Dr. Jacob Alexander)

Stomach bots (gastric myiasis)

Asian elephants are susceptible to infestations caused by Cobboldia elephantis. Adult flies lay eggs at the base of the tusk or tusk sulcus. Eggs are ingested and hatch in the stomach. In mild cases signs include loose stool, mouth breathing, and mud eating. Diarrhea, loss of appetite, colic, and anemia may be seen in severe cases (Mar, 2006) Heavy infestations have the possibility of causing gastric rupture. Ivermectin or trichlorfon are effective. Camphor oil or neem oil can be applied to the base of the tusks as a repellent (Mar, 2006).

Click here to read more about the morphology of the larves found in the elephant's stomach.

Some eggs may already hatch on the skin and the larvae may migrate to the tusk sulcus and cause a sulcus infection; click here to read a case report about such a sulcus infection.

Bots (larvae) of Cobboldia sp. found in the stomach of an Asian elephant (Dr. Vijitha Perera)

Endoparasites

Elephants are affected by three major groups of parasites:

-

Nematodes: roundworms like ascarids, stronygles, strongyloides, and hookworms

-

Trematodes: flatworms like liver flukes (Fasciola elephantis)

-

Cestodes: tapeworms like anoplocephala

In healthy wild elephants parasites often live in balance with their hosts without causing any obvious harm. However, any number of environmental stressors can upset this balance and result in clinical disease even in adults.

Orphan calves are often under tremendous physiological and/or mental stress resulting from lack of food, separation from the herd, or injuries. So it is important to determine what parasites they are harboring and to administer appropriate anthelmintic (de-worming) medications. Parasites that may not have been a problem for a healthy calf can be deadly for a traumatized orphan.

If in an orphanage the eggs per gram count of nematodes is high, calves should be dewormed using fenbendazole, albendazole, levamisole, or ivermectin. If there are Fasciola eggs in the feces, they are treated with triclabendazole and if Anoplocephala eggs are found they are treated with praziquantel.

The prevalence of various parasites may vary with geographical location and environmental factors. Flukes, for example require water and the presence of an intermediary host (snails).

General signs of parasite infections include weakness, poor skin and body condition, diarrhea, poor appetite, a tendency to eat mud, and in the case of blood sucking parasites, anemia. Submandibular or ventral edema may be seen.

Some adult parasites may be seen in the feces but most reside deep within the intestinal tract. It is always advisable to perform a fecal examination to look for parasites eggs under the microscope.

The presence of endoparasites may in some instances be reflected in the consistency of the feces. Monitoring the quality of the feces is an important tool to monitor the digestion of food and the presence of endoparasites.

Nematodes

Toxocara elephantis

Toxocara elephantis infection has been reported in an Asian elephant from a zoo in Switzerland

(Fowler & Mikota 2008) and in a 5 yrs-old wild Asian elephant after being rescued from a flood (Bora et al. 2019). Clinical examination revealed normal body temperature (36.4°C), congested conjunctival mucous membranes, increased pulse rate (38 bpm) and eupnoea (14 breaths/min). Microscopic examination of the faecal sample showed the presence of T. elephantis

ova, which were round-shaped with a thick outer shell.

The animal was treated with albendazole at 10 mg/kg, orally, once daily for 3 days and received supportive therapy for 7 days, after which it had recovered completely.

Click here for the complete manuscript.

Blood parasites

Trypanosomiasis (Surra, Thut)

Trypanosomiasis is a protozoan disease transmitted by biting flies and mosquitoes. It is most prevalent in Asia during the rainy season. Clinical signs may include fever, extreme weakness, lethargy, dry skin, anemia, and a progressive loss of body condition leading to emaciation. Constipation or diarrhea may be present or feces may be normal. Edema of the face, trunk, neck, lower abdomen, and limbs may be seen (Desquesnes et al., 2013). Characteristic organisms can be seen on blood smears collected during episodes of fever. An ELISA has also been developed and used for a serosurvey in Thailand (Camoin et al., 2018). Cases have been reported in Myanmar, Thailand, and India. However, Surra does not seem to be common in Sri Lanka and may be most likely to occur when elephants are in close proximity to infected cattle or buffalo. Diminazene aceturate is recommended for treatment, however the dosage is controversial. Three elephants in Thailand treated with 5 mg/kg relapsed (Desquesnes et al., 2013). A single elephant was successfully treated increasing the dosage to 7-8 mg/kg (Rodtian et al., 2012) but the drug is known to have serious side effects so should be used with caution.

Babesia (Babesiosis, Piroplasmosis, Tick Fever)

Babesiosis is a tick-transmitted protozoan disease. It has rarely been reported in Asian elephants (McGaughey, 1961) and even in African elephants there are only a few publications (Brocklesby and Campbell, 1963; King'ori et al., 2019). Clinical signs may include weakness, fever, jaundice, constipation, and hemoglobinuria. Characteristic organisms can be seen on blood smears. Three elephants diagnosed with babesiosis in Sri Lanka responded well to diminazine aceturate at a dosage of 3.5–7.0 mg/kg (personal communication Dr. ID Silva, Sri Lanka, 2005).

Filaria parasites

Filaria are a group of nematodes that live in the tissue of vertebrates; filariasis refers to the presence of microfilaria in blood and tissues. Indofilaria spp. cause a cutaneous filariasis that results in 1–2 cm nodules on the sides, lower abdomen, and limbs (Chandrasekharan, 2002). Stephanofilaria spp. cause lesions on the back and ventral areas (Bhattacharjee, 1970) or on the feet (Tripathy et al., 1989; Tripathy and Das, 1992). Microfilaria can be seen in blood that oozes from ruptured nodules and also in the peripheral blood. Other clinical signs of cutaneous filariasis may include restlessness, dry skin, and submandibular or ventral edema. Diagnosis is by observing the motile parasites on a blood smear that is best collected between 9 PM and 3 AM (Mar, 2006). Heavy infections can be treated with ivermectin given every 4–6 months (Mar, 2006)

Cutaneous Filariasis in Elephants

Introduction

Cutaneous filariasis is a parasitic disease affecting elephants, caused by various species of filarial nematodes. These microscopic worms inhabit the skin and subcutaneous tissues, leading to chronic skin lesions in affected elephants, often associated with itching. This condition is more commonly observed in Asian elephants but can also affect African elephants.

Etiology and Transmission

The primary causative agents of cutaneous filariasis in elephants are nematodes from the genera Stephanofilaria, Setaria, and Onchocerca. These parasites are transmitted by blood-feeding arthropods that serve as intermediate hosts. The larvae enter the host during feeding, eventually developing into adult worms in the skin tissues.

Clinical Signs

Elephants with cutaneous filariasis often exhibit the following symptoms:

-

Nodular or ulcerative skin lesions

-

Thickened, rough, or depigmented skin

-

Pruritus (itching) and discomfort

-

Secondary bacterial infections due to constant irritation and scratching. Lesions are frequently found around the head, trunk, and legs, although they can occur on any part of the body.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of cutaneous filariasis involves a combination of clinical examination and laboratory analysis. Biopsies from lesions are examined under a microscope to detect microfilariae. Molecular techniques, such as PCR on blood samples, can provide more precise identification of the filarial species (Saengsawang, 2023).

Clinically the lesions look like lumps caused by dipterous flies. Dipterous larva may produce small nodular eruptions from which larva can be expressed (Chakraborty, 2003). When the larva is mature, the fly exits, leaving a small hole in the skin. Secondary infections may develop that are usually bacterial, but mycotic dermatitis has also been recorded.

Treatment and Management

Treatment involves the administration of antiparasitic drugs such as ivermectin. This medication targets microfilariae and adult worms, reducing the parasite load. Regular application of insect repellents can help prevent further transmission by reducing vector bites.

Dosage Ivermectin Guidelines for Elephants:

-

There is no scientific study on the efficacy of ivermectin in cutaneous filariasis. Anecdotally dosages used range from 0.1-0.3 mg/kg SQ or PO (Case report: Dayashankar, 2023).

-

Severe or resistant Cases: up to 0.4 mg/kg

-

Frequency: administered once every 2 weeks for 2 to 3 treatments. In some cases, monthly doses may be needed for long-term prevention.

Important considerations:

-

Microfilariae die-off: rapid killing of microfilariae can lead to inflammatory reactions or swelling. To mitigate this, anti-inflammatory medications (e.g., corticosteroids) may be given concurrently. This phenomenon, however, has never been reported in elephants.

-

Supportive Treatment: Address secondary infections or ulcerations with antibiotics and topical antiseptics.

Prevention and Control

Preventive measures include minimizing exposure to biting insects through habitat management, use of insect repellents, and protective coverings for captive elephants. Routine veterinary check-ups and antiparasitic treatments can help identify and manage early infections, reducing the risk of widespread outbreaks.

References

-

Bhattacharjee, M.L., 1970. A note on stephanofilarial dermatitis among elephants in Assam. Sci. Cult 36, 600-601.

-

Bora N, Ali S, Sarma K, Roychoudhury P, Eregowda C.G., Prasad H., Rajesh J.B., Mohanarao G.J., Behera S.K., Das D. and Choudhury B. 2021. Toxocara elephantis Infection in a Juvenile Asian Elephant and Its Management. Gajah, 54 (40-44).

-

Brocklesby, D.W., Campbell, H., 1963. A babesia in the African elephant. East Afr. Wildl. J 1, 119.

-

Camoin, M., Kocher, A., Chalermwong, P., Yangtarra, S., Thongtip, N., Jittapalapong, S., Desquesnes, M., 2018. Adaptation and evaluation of an ELISA for Trypanosoma evansi infection (surra) in elephants and its application to a serological survey in Thailand. Parasitology 145, 371-377.

-

Chakraborty, A. 2003. Diseases of elephants (Elephas maximus) in India—A review. Indian Wildl Yrbk 2:74–82.

-

Chel, H.M. et al. 2020. Morphological and molecular identification of cyathostomine

gastrointestinal nematodes of Murshidia and Quilonia species from Asian

elephants in Myanmar. IJP: Parasites and Wildlife 11, 294–301. -

Dayashankar and Rakesh Kumar Singh. 2023. Management of Filariasis in Asian Elephants (Elephus Maximus) Under Field Conditions. Acta Scientific Veterinary Sciences (ISSN: 2582-3183) Volume 5 Issue 5 May 2023.

-

Desquesnes, M., Holzmuller, P., Lai, D.H., Dargantes, A., Lun, Z.R., Jittaplapong, S., 2013. Trypanosoma evansi and surra: A review and perspectives on origin, history, distribution, taxonomy, morphology, hosts, and pathogenic effects. BioMed research international 2013.

-

Fowler, M.A., 2006. Parasitology. In: Fowler, M.A., Mikota, S.K. (Eds.), Biology, Medicine, and Surgery of Elephants. Blackwell, Ames Iowa, 159-181.

-

Karesh, W.B., Robinson, P.T., 1985. Ivermectin treatment of lice infestations in two elephant species. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc 187, 1235-1236.

-

Kavitha, K.T., C. Sreekumar & B.R. Latha (2022). Case report of hook worm Grammocephalus hybridatus and stomach bot Cobboldia elephantis infectons in a free-ranging Asian Elephant (Elephas maximus) in Tamil Nadu, India. Journal of Threatened Taxa 14(4): 20915–20920. htps://doi.org/10.11609/ jot.6910.14.4.20915-20920.

-

King'ori, E., Obanda, V., Chiyo, P.I., Soriguer, R.C., Morrondo, P., Angelone, S., 2019. Molecular identification of Ehrlichia, Anaplasma, Babesia and Theileria in African elephants and their ticks. PLoS One 14, e0226083.

-

Mar, K.U., 2006. Veterinary Problems of Geopgraphical Concern: Myanmar. In: Fowler, M.A., Mikota, S.K. (Eds.), Biology, Medicine, and Surgery of Elephants. Blackwell, 460-464.

-

Matsuo K, and Ssuprahman H. 1997. Some parasites from Sumatran elephants in Indonesia. Journal of the helminthological society of Washington, 64(2), july 1997, 298,299.

-

Perera B.V.P., Rajapakse R.P.V, Thewarage L.D., Silva_Fletcher A., 2015. Mortality of wild Sri Lankan elephants (Elephas maximus) as a result of Parabronema smithi infestation. Proc Int Conf Dis Zoo Wild Anim 2015.

-

Perera B.V.P., Rajapakse R.P.V.J., Abeywardana M.K. 2011. Prevalence of Cobboldia elephantis in free ranging elephants in Sri Lanka. Elephant and Rhino Conservation & Research Symposium organized by International Elephant Foundation, October 2011.

-

Perera B.V.P., Rajapakse R.P.V.J., Abeywardana M.K., Pinidiniya M.A., Silva-Fletcher A. 2018. Population threshold and emerging parasitic disease of elephants in Sri Lanka. Joint EAZWV/AAZV/ Leibniz-IZW conference 2018.

-

Rodtian, P., Hin-on, W., Muangyai, M., 2012. A Success Dose of Eight mg per kg of Diminazene Aceturate in a Timber Elephant Surra Treatment: Case Study. . In, First Regional Conference of the Society for Tropical Veterinary Medicine (STVM): A change in global environment, biodiversity, diseases and health, Thailand, 24.

-

Saengsawang P, Desquesnes M, Yangtara S, Chalermwong P, Thongtip N, Jittapalapong S, Inpankaew T. 2023. Molecular detection of Loxodontofilaria spp. in Asian elephants (Elephas maximus) from elephant training camps in Thailand. Comparative Immunology, Microbiology and Infectious Diseases Volume 92, January 2023.

-

Sey O.1985. Amphistomes of Vietnamese vertebrates (Trematoda: Amphistomida).Parasit, Hung. 18. 1985.

-

Tripathy, S.B., Das, P.K., 1992. Treatment of Stephanofilarial dermatitis in an Asian elephant (Elephas maximus): a case report. In: Silas, E.G., Nair, M.K., Nirmalan, G. (Eds.), The Asian Elephant: Ecology, Biology, Diseases, Conservation and Management (Proceedings of the National Symposium on the Asian Elephant held at the Kerala Agricultural University, Trichur, India, January 1989). Kerala Agricultural University, Trichur, India, 162-163.

-

Tripathy, S.B., Das, P.K., Acharjya, L.N., 1989. Treatment of microfilarial dermatitis in an Asian elephant (Elephas maximus): a case report. Indian Journal of Indigenous Medicines, 31-33.

-

Windsor R.S.,and Scott W. 1976. Fasciolasis and Salmonellosis in African elephants in captivity. Br. vet.]. (1976), 132, 313.